Née en 1987, Justine Emard est une artiste qui aime faire dialoguer créations et nouvelles technologies. Après des études aux Beaux Arts, c’est au cours d’une résidence en 2010 dans un centre de Réalité Virtuelle, qu’elle a réellement découvert le monde informatique, qu’elle a voulu apprendre à coder et s’immerger dans le monde des technologies afin d’y apporter son regard critique. Ses dispositifs prennent pour point de départ des expériences de Deep-Learning (apprentissage profond) et de dialogue entre l’humain et la machine. Depuis, elle est reconnue internationalement au Japon, au Canada en passant par l’Allemagne pour mettre en scène la rencontre plastique des intelligences humaines et artificielles. À travers ses protocoles, où elle laisse une part à l’imprévisible, elle fait ressortir la singularité de chacun entre perfection technique et créativité humaine, entre patrimoine culturel et innovation scientifique. En 2020, elle est en résidence au ZKM, Centre d’Art et des Médias Karlsruhe, et elle est lauréate de la commande nationale photographique “IMAGE 3.0” du Centre national des arts plastiques (CNAP) en partenariat avec le Jeu de Paume à Paris. En 2021-22, elle est artiste-professeure invitée au Fresnoy, Studio national des arts contemporains et est en résidence hors-les-murs en 2022 à l’Observatoire de l’Espace, le laboratoire culturel du CNES.

Pourquoi avez vous choisi de devenir artiste ? Quelle est selon vous votre première oeuvre ?

« Je n’ai pas vraiment choisi de devenir artiste. Comme j’ai toujours crée des formes et des images, c‘était très naturel de m’orienter vers une voie artistique. Cela a guidé mes choix depuis mon enfance jusqu’à ma vie adulte.

Je me souviens quand j’étais enfant on m’avait emmenée voir la grotte de Lascaux, ou plutôt son fac similé. J’étais très déçue de voir la copie, je n’avais pas compris l’intérêt. J’ai alors ramassé sur le bord de la route de la terre et des pigments et j’ai peint un cerf sur une petite ardoise. Peut-être avais je eu besoin de retrouver une forme d’authenticité par le geste et la matière en dessinant ce petit cerf ?

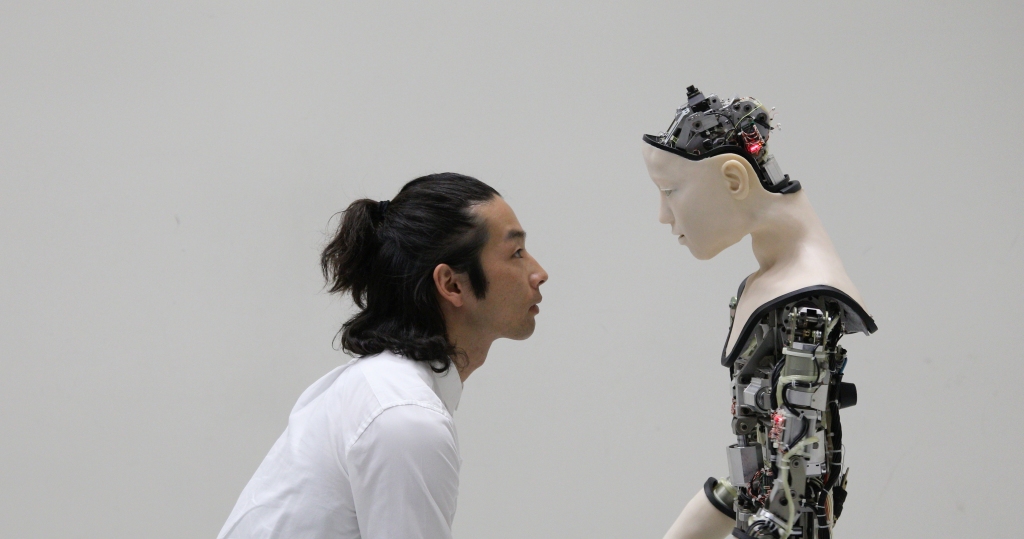

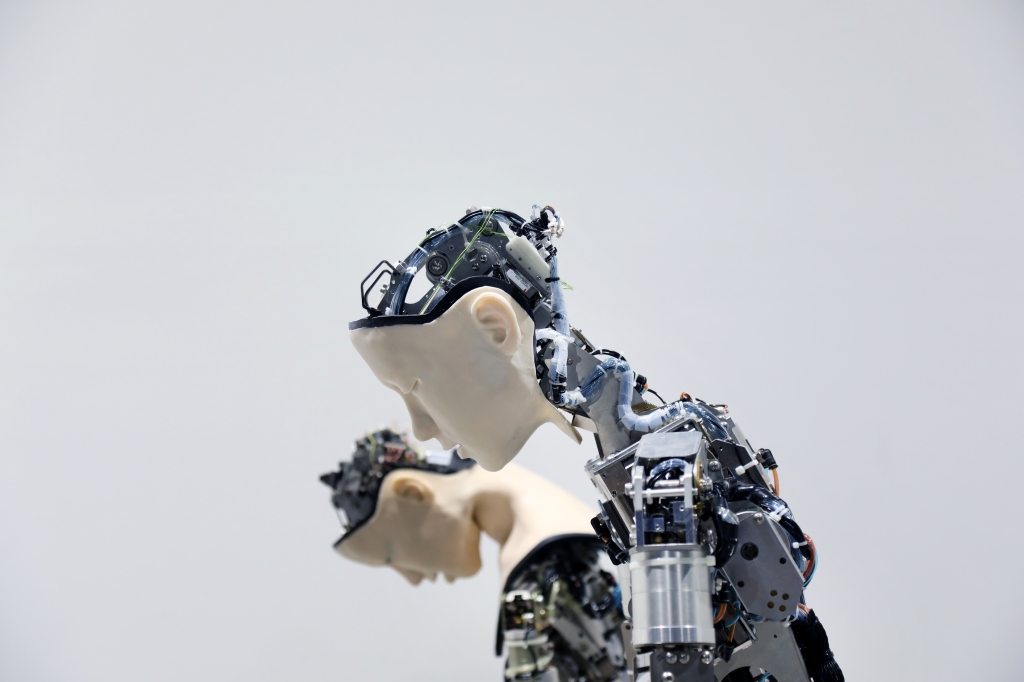

( Avec Alter et Alter 2, développés par Ishiguro Lab, Université d’Osaka et Ikegami Lab, Université de Tokyo)

Quelle serait votre définition de l’art ?

Je cherche, comme tout artiste, à délivrer une experience que j’ai du monde. L’art est une recherche, on y crée des outils, tel un scientifique, pour mesurer et interpréter le monde. C’est un long chemin pour arriver à ces visions que nous communiquons ensuite à nos contemporains. Oui il m’est arrivé plusieurs fois de collaborer avec des scientifiques pour interpréter le monde d’aujourd’hui. Plutôt que de rester dans la science-fiction, je préfère délivrer une expérience du présent.

Qu’est que l’art apporte à la science ?

Je dirais qu’une collaboration est réussie, quand les deux univers s’apportent quelque chose mutuellement. J’aime travailler avec des objets scientifiques pour aller vers des installations artistiques et défricher de nouveaux territoires. J’aime travailler sous forme de protocoles, mais je laisse toujours une grande part à l’imprévisible que je valorise, alors que le protocole scientifique est très rigoureux et ne vous autorise pas à aller dans certaines directions. J’aime cette porosité entre art et science, car nous vivons dans le même monde.

Installation vidéo, 2017, 12′

(Avec Mirai Moriyama & Alter- développés par Ishiguro Lab, Université d’Osaka et Ikegami Lab, Université de Tokyo)

Co(AI)xistence est une installation vidéo de 12 minutes. Dotés d’intelligences différentes, l’humain et le robot dialoguent à travers les signaux de leurs langages respectifs, tant corporels que verbaux. En utilisant un système d’apprentissage profond non anthropomorphique (Deep Learning), le robot peut apprendre de sa rencontre avec le danseur, Mirai Moriyama et réciproquement. Cette experience nous interroge : comment peuvent ils malgré leur différence créer quelque chose ensemble? Le robot Alter, est animé par une forme de vie primitive basée sur un système neuronal, une intelligence artificielle (IA) programmée par le laboratoire de Takashi Ikegami (Université de Tokyo), dont l’incarnation humanoïde a été créée par le laboratoire de Hiroshi Ishiguro (Université d’Osaka). Son apparence minimale autorise une projection émotionnelle, en ouvrant un espace pour l’imagination. L’oeuvre a été créée avec un protocole qui a nécessité une grande préparation technologique afin de garder une forme d’imprévisibilité.

Keiichiro Shibuya + Eizen Fujiwara + Justine Emard

Monastery of the Canons Regular of St. Augustine’s Order at St. Florian, Linz, Austria

Keiichiro Shibuya + Eizen Fujiwara + Justine Emard

St. Florian, Linz, Austria

La Vision des Machines (2019) est née d’une performance Heavy Requiem pour laquelle j’ai travaillé avec un compositeur de musique électronique et un moine bouddhiste. C’est une experience assez mystique, elle a eu lieu une fois dans un monastère à Linz pendant Ars Electronica. J’ai animé des scans 3D que j’ai captés dans les montagnes sacrées du Japon, à Koya San, qui réagissent en temps réel à la voix du moine bouddhiste. C’est une incarnation de ces chants ancestraux connus sous le nom de shomyo qui ont une histoire de 1200 ans, les classant avec le chant grégorien occidental comme l’une des plus anciennes formes vivantes du genre. C’était une exposition sur la rencontre entre l’intelligence artificielle et la musique, la créativité humaine et la perfection technique. La musique peut être la plus émotive de toutes les formes d’art, mais elle est aussi profondément liée aux mathématiques, à la physique de la production sonore et à l’artisanat des fabricants d’instruments. Cela signifie que, dès le début, l’histoire de la musique est aussi l’histoire des instruments, des outils et des dispositifs nécessaires pour la jouer, l’enregistrer et la reproduire.

L’origine des images est une recherche initiée en 2019 avec le chercheur canadien Sofian Audry et que je continue cette année dans le cadre de l’invitation faite par le Fresnoy en tant qu’artiste-professeure invitée. Il s’agit d’entrainer une intelligence artificielle sur des photographies de peintures pariétales, de manière à créer de nouvelles images. Pour la première fois depuis la préhistoire, nous avons franchi une étape importante : la majorité des images produites dans le monde n’est pas destinée à être vue par l’œil humain, mais plutôt par des machines. Les réseaux neuronaux artificiels (une branche de l’intelligence artificielle) apprennent à reconnaître les images, à détecter les formes et à les imiter, voire à créer de nouvelles images de manière autonome, sans intervention humaine.

Nous entrainons des réseaux de neurones artificiels sur une collection d’images de peintures rupestres. En observant ces images, ces réseaux de neurones développent progressivement leur propre appareil perceptif autour de l’univers visuel des peintures analysées : couleurs, formes floues, puis éventuellement silhouettes et profils d’animaux apparaissent, révélant une nouvelle forme de perception des premières œuvres humaines.

Avez vous des projets en Réalité Virtuelle ou Augmentée ? en NFT ?

J’ai travaillé avec la Réalité Augmentée dès 2010 lors d’une de mes premières résidences où j’ai commencé à programmer pour Screencatcher (2011) une installation qui mêle dessin et technologie. Au départ c’est une enquête sur la disparition des cinémas de plein air américains. Je présente une série de quinze dessins au feutre, de driver-in theaters laissés à l’abandon, que le spectateur est invité à regarder s’animer à travers son écran de téléphone ou de tablette. Grâce à un logiciel, des vidéos se superposent aux dessins et augmentent l’espace dessiné d’une réalité virtuelle et proposent ainsi une expérience inédite du paysage.

Plus récemment, pour la commande photographique IMAGE 3.0 du Cnap, j’ai créé avec une interface cerveau-machine. Ce dispositif de contrôle numérique basé sur l’attention visuelle, développé avec des neuroscientifiques, rend tangible l’interaction entre le cortex visuel de notre cerveau et un monde virtuel. La matière se reconfigure dans des imaginaires liés à la plasticité neuronale en hommage à notre capacité de génération du cinéma intérieur.

Installation (verre soufflé, robotique, capteurs et système de machine learning), 2020 Photo Caroline Lessire

Installation (verre soufflé, robotique, capteurs et système de machine learning), 2020 Photo Caroline Lessire

Quelles sont vos sources d’inspiration ?

La manière dont les architectes travaillent de manière décomplexée avec la technologie et la science, comme par exemple Zaha Hadid ou le design de modélisation paramétrique. Je suis sensible aux environnements que crée Hito Steyerl, aux écrits de la philosophe Catherine Malabou et sa pensée sur la plasticité, mais aussi aux récits du paléontologue Yves Coppens et de Jean-Michel Geneste, qui sont des personnes majeures dans la découverte de notre humanité.

Quelles sont les différences de perception en fonction des pays et des cultures où vos oeuvres sont présentées ?

Sans tomber dans le cliché, elles correspondent aux différents rapports entretenus avec la technologie et l’art, surtout avec la question éthique qui est souvent pensée différemment. Au Japon, la robotique et l’intelligence artificielle sont tournées pour répondre à des problèmes de société. Ils ont une compréhension émotionnelle des œuvres. En Europe, je dirai que l’approche est plus intellectuelle et philosophique. Sur le continent américain, on est à la frontière entre plusieurs mondes, dont celui des industries créatives. Ils ont un rapport fonctionnel à l’objet, les œuvres prennent souvent le sens du détournement de cette fonctionnalité. À ce sujet, je suis en faveur des livres d’or dans les expositions, nous avons ainsi des retours passionnants sur l’experience de l’exposition. Comme c’est anonyme, je pense que c’est plus honnête que sur les réseaux sociaux.

Vos conseils à un(e) jeune artiste ?

Je dirai que la clé c’est la détermination. Qu’il-elle aura certainement beaucoup d’obstacles à franchir, qu’il est important de ne pas se laisser détourner. Et il faut oser aller vers ce qu’on ne connait pas et les choses qui nous font peur.

Prototypes : Hyperphantasia, les rêves de l’espace

Justine Emard

Cinq impressions 3D, 2022

Photographie : Julien Bruhat

Justine Emard

Cinq impressions 3D, 2022

Photographie : Julien Bruhat

Quels sont vos projets ?

En 2022, je suis en résidence hors-les-murs à l’Observatoire de l’Espace , le laboratoire culturel du CNES (Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales) pendant un an. Cette résidence me permet de travailler en collaboration avec le milieu spatial, plus particulièrement sur les rêves en micro-gravité, sachant que le cerveau fonctionne différemment en apesanteur.

Je m’intéresse à l’évolution du sommeil avant, pendant et après un séjour dans l’espace. C’est un travail en collaboration avec la neurologue Rachel Debs (CHU de Toulouse), qui étudie le sommeil au cours des voyages spatiaux dans le cadre de l’expérience DREAMS avec l’ESA. À partir des mesures encéphalographiques d’astronautes, je vais composer une série d’œuvres dont un paysage de sculptures imprimées en 3D pour matérialiser les rêves. J’ai créé un protocole, entre neurosciences et sculptures, pour imprimer ces rêves en trois dimensons grâce à un bras robotique industriel. Il s’agit de produire des formes en céramique à partir de signaux enregistrés au plus profond de notre inconscient, et de révéler une signature neuronale architecture mentale. Le résultat de cette recherche sera présenté au sein d’une installation au Fresnoy à l’occasion de l’exposition PANORAMA 24 à l’automne 2022.

Interview réalisée par Valentine Meyer le 2 Février 2022. Chaleureux remerciements à Justine Emard. Pour connaitre son actualité et plus encore, voici le lien vers son site

Justine Emard, art as a meeting place between human and artificial intelligences

Co(AI)xistence, Justine Emard

Installation vidéo, 2017, 12′

(Avec Mirai Moriyama & Alter- développés par Ishiguro Lab, Université d’Osaka et Ikegami Lab, Université de Tokyo)

Born in 1987, Justine Emard is an artist who likes to bring together creations and new technologies. After studying at the Beaux Arts, it was during a residency in 2010 in a Virtual Reality center, that she really discovered the computer world, that she wanted to learn to code and to immerse herself in the world of technologies in order to bring her critical look. Her devices take as a starting point the experiences of Deep-Learning and dialogue between the human and the machine. Since then, she has been recognized internationally in Japan, Canada and Germany, to name few, to stage the plastic encounter of human and artificial intelligences. Through her protocols, where she leaves a part to the unpredictable, she brings out the singularity of each one between technical perfection and human creativity, between cultural heritage and scientific innovation. In 2020, she is in residence at the ZKM, Centre d’Art et des Médias Karlsruhe, and is the winner of the national photographic commission “IMAGE 3.0” from the Centre national des arts plastiques (CNAP) in partnership with the Jeu de Paume in Paris. In 2021-22, she was a guest artist-professor at the Fresnoy, Studio national des arts contemporains and is in residence outside the walls in 2022 at the Observatoire de l’Espace, the CNES cultural laboratory.

Why did you choose to become an artist? What do you think is your first artwork?

I didn’t really choose to become an artist. As I have always created shapes and images, it was very natural to orient myself towards an artistic path. It guided my choices from childhood to adulthood.

I remember when I was a kid I was taken to see the Lascaux Cave, or rather its facsimile. I was very disappointed to see the copy, I didn’t understand the interest. I then picked up on the side of the road some dirt and pigments and I painted a deer on a small slate. Maybe I needed to find a form of authenticity through gesture and matter by drawing this little deer?

What would be your definition of art?

I seek, like any artist, to deliver an experience that I have of the world. Art is research, it creates tools, like a scientist, to measure and interpret the world. It is a long way to arrive at these visions that we then communicate to our contemporaries. Yes, I have worked several times with scientists to interpret the world today. Rather than remain in science fiction, I prefer to deliver an experience of the present.

What does art bring to science?

I would say that a collaboration is successful, when the two universes bring something to each other. I like working with scientific objects to go to artistic installations and clear new territories. I like to work in the form of protocols, but I always leave a lot to the unpredictable that I value, whereas the scientific protocol is very rigorous and does not allow you to go in certain directions. I like this porosity between art and science, because we live in the same world.

Co(AI)xistence is a 12-minute video installation. Endowed with different intelligences, the human and the robot dialogue through the signals of their respective languages, both corporeal and verbal. By using a non-anthropomorphic deep learning system, the robot can learn from his encounter with the dancer, Mirai Moriyama and vice versa. This experience questions us: how can they despite their difference create something together? The Alter robot, is driven by a primitive life form based on a neuronal system, an artificial intelligence (AI) programmed by the laboratory of Takashi Ikegami (University of Tokyo), whose humanoid incarnation was created by the laboratory of Hiroshi Ishiguro (University of Osaka). Its minimal appearance allows an emotional projection, opening a space for the imagination. The work was created with a protocol that required a great technological preparation in order to keep a form of unpredictability.

La Vision des Machines (2019) was born from Heavy Requiem performance for which I worked with an electronic music composer and a Buddhist monk. It is a rather mystical experience, it took place once in a monastery in Linz during Ars Electronica. I animated 3D scans that I captured in the sacred mountains of Japan, in Koya San, which react in real time to the voice of the Buddhist monk. It is an embodiment of those ancestral chants known as shomyo, which have a 1200-year history, classifying them with Western Gregorian chant as one of the oldest living forms of the genre. It was an exhibition on the encounter between artificial intelligence and music, human creativity and technical perfection. Music can be the most emotional of all forms of art, but it is also deeply linked to mathematics, the physics of sound production and the craft of instrument makers. This means that, from the beginning, the history of music is also the history of the instruments, tools and devices needed to play, record and reproduce it.

The origin of the images is a research initiated in 2019 with Canadian researcher Sofian Audry and which I continue this year as part of the invitation made by the Fresnoy as a guest artist-professor. It is a matter of training an artificial intelligence on the photographs of parietal paintings, in order to create new images. For the first time since prehistory, we have taken an important step: the majority of images produced in the world are not intended to be seen by the human eye, but rather by machines. Artificial neural networks (a branch of artificial intelligence) learn to recognize images, detect and imitate shapes, or even create new images autonomously, without human intervention.

We were training artificial neural networks on a collection of images from cave paintings. By observing these images, these neural networks gradually develop their own perceptive apparatus around the visual universe of the paintings analyzed: colors, fuzzy shapes, then possibly silhouettes and profiles of animals appear, revealing a new form of perception of the first human works.

Vidéo, 2018, 6′

( Avec Alter et Alter 2, développés par Ishiguro Lab, Université d’Osaka et Ikegami Lab, Université de Tokyo)

Do you have projects in Virtual Reality or Augmented Reality? in NFT?

I worked with Augmented Reality since 2010 during one of my first residencies where I started programming for Screencatcher (2011) an installation that mixes design and technology. Initially it’s an investigation into the disappearance of American open-air cinemas. I present a series of fifteen drawings with felt, of driver-in theaters left to the abandonment, that the spectator is invited to watch coming alive through his screen of phone or tablet. Thanks to software, videos are superimposed on the drawings and increase the space drawn of a virtual reality and thus offer a unique experience of the landscape.

More recently, for the Cnap’s (National Center for Visual Art) IMAGE 3.0 photographic commission, I created with a brain-machine interface. This digital control device based on visual attention, developed with neuroscientists, makes tangible the interaction between the visual cortex of our brain and a virtual world. Matter is reconfigured in imaginations linked to neuronal plasticity in homage to our ability to generate indoor cinema.

What are your sources of inspiration ?

The way in which architects work in an uninhibited way with technology and science, such as Zaha Hadid or parametric modeling design. I am sensitive to the environments created by Hito Steyerl, to the writings of the philosopher Catherine Malabou and her thought on plasticity, but also to the narratives of the paleontologist Yves Coppens and Jean-Michel Geneste, who are major figures in the discovery of our humanity.

What are the differences in perception depending on the countries and cultures where your works are presented?

Without falling into cliché, they correspond to the different relationships with technology and art, especially with the ethical question that is often thought differently. In Japan, robotics and artificial intelligence are turned to address social problems. They have an emotional understanding of works. In Europe, I would say that the approach is more intellectual and philosophical. On the American continent, we are on the border between several worlds, including the creative industries. They have a functional relationship to the object, the works often take the sense of diversion of this functionality. In this regard, I am in favour of the golden books in the exhibitions, so we have exciting feedback on the experience of the exhibition. Since it’s anonymous, I think it’s more honest than social media.

Your advice to a young artist?

I’d say the key is determination. It will certainly have many obstacles to overcome, which it is important not to be distracted. And we must dare to go to what we don’t know and the things that frighten us.

What are your plans?

In 2022, I am in residence outside the walls at the Observatoire de l’Espace, the CNES cultural laboratory (National Center for Space Studies). This residency allows me to work in collaboration with the space community, especially on dreams in micro-gravity, knowing that the brain functions differently in weightlessness.

I am interested in the evolution of sleep before, during and after a stay in space. This is a collaboration with neurologist Rachel Debs (Toulouse CHU), who is studying sleep during space travel as part of the DREAMS experiment with ESA. Based on astronaut encephalographic measurements, I will compose a series of works including a landscape of 3D printed sculptures to materialize dreams I created a protocol, between neurosciences and sculptures, to print these dreams in three dimensions thanks to an industrial robotic arm. It involves producing ceramic shapes from signals recorded deep in our unconscious, and revealing a neural signature mental architecture. The result of this research will be presented in an installation at the Fresnoy on the occasion of the exhibition PANORAMA 24 in autumn 2022.

Interview conducted by Valentine Meyer on February 2, 2022. Warm thanks to Justine Emard. To know its news and more, here is the link to her website